Orchard Chronicles

An Investigation into Inequality and the Ground

2018

Linkages in Inequality

Various aspects in relationship

Positioning Inequality

OWNERSHIP, ACCESS, ENCLOSURES

What is inequality?

Or to be more precise, what are its implications on space, form and order? This book sketches a partial understanding of inequality in architectural terms, specifically to the public realm of public and social spaces. By ‘inequality’, we mean not just the measurable income gap of the socio-economic class divide between the rich and the poor, but rather, we extend to include the different stakeholders and agents of the city: the different groups of communities and sub-cultures in a particular place, the different economic positions as owners and wage workers, the native and the strangers; all with their individual and collective, conflicting interests in the city (Martin 2015).

From a historical survey of the past 200 years, we saw how the technological revolution transformed the economy and therein, changing the way we live (Rifkin 2015). As our society structure becomes more complex, the state of governance became increasingly

intertwined with the free, capital, presently neoliberal market. State policies affirms the capitalistic market, thus create a structure of discrimination and differentiation (Teo 2018). In many states, policies have differentiated the needs of and assistance to the people based on income brackets imposed by the capital market (Teo 2018). In doing so, gradually, people in the society live with labels: the rich, the poor, the powerful. In turn, people need to negotiate with these labels in addition to issues like gender, race and nationalities, all of which aggravate the notions of the labels, especially for underprivileged groups (Puthucheary 2018 ). These notions of inequality are then physicalized in their everyday experiences and rituals of their living environment. Its effects are fell through the course of history, from the process of production of goods and services to consumption centres where good and services are exchanged (Rifkin 2015).

In a physical form, the malls, markets, neighbourhood centres are the urban marketplaces of today in which they function as shared public spaces which facilitate this exchange. Inequality, through architecture, sharpens the notion of class divide (Martin 2015). It becomes a physical comparison of who has a bigger house, who has access to Michelin-starred restaurant, who is living on social assistance. Consequently, the physical environment shapes the way we think about ourselves and others.

Just as Winston Churchill once said, ‘We shape building; thereafter buildings shape us’. Do we want to shape our living environment as a space of contestations and segregations? Or are we able to create a space that tolerates and welcomes the repertoire of differences and interests?

Can we co-exist together on a single plane?

Diverse Viewpoints

The first who, having enclosed a piece of land is thought of saying This is mine, and found people simple enough to believe, was the true founder of civil society.

Jean Jacques Rousseau

As 19th century philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau (who lived in the height of the 1st Industrial Revolution) had said, the state of inequality is of artificial nature, moral constructs of the act of man seeking to govern and order the society (Rousseau 2018). Man had legitimize the hierarchies of power and wealth through governance and manifested in the ownership of property rights (Rousseau 2018). Yet, however, he also mentioned that it is impossible to also return to the state of nature to restore equality as we become attuned to this living environment (Rousseau 2018).

Politically, in more recent times, inequality was also acknowledged by the state as a pertinent problem that persist since colonial times. It is a question of relativities and balancing the different forces at work. It is not a solution based on capping the growth of at the top of the society (Yahya 2018 ). Rather, perhaps, to close the gap by lifting the bottom of the society through providing access (Ong 2018). Social mobility is key to bridging the gap. As long as the ‘moving escalator’ continue to bring people up through policies of housing, healthcare and most importantly education, the different stratification of the society can

co-exist together in the city (DPM Tharman Shanmugaratnam 2018).

In terms of social aspect, sociologist Teo You Yenn’s book This is what inequality looks like is a timely literature that reveals the interlinkages of those contestations happening in the lives of people living in the margins of inequality. It is a documentation that goes beyond numbers, of the everyday lived experiences of people in the lower brackets of society, contrasting with the people on the upper tier (Teo 2018). In which, she pauses to reflect that inequality is not just about ‘them’, rather, it is also about ‘us’. Hence, the issue of inequality is intertwined with social agendas like dignity, family and everyday lives.

In addition, the French economist Thomas Piketty in his 2013 Capital in the Twenty-First Century book, elucidated the wealth and income inequality in Europe and the United States since the 18th century (Piketty 2017). The central thesis of his book was that as the rate of return on capital (r) is greater than the rate of economic growth (g) over the long term, the result is concentration of wealth, and this unequal distribution of wealth causes social and economic instability (Piketty 2017). In simpler terms, as ownership of resources in the hands of wealthy capital investors would experience investment returns that are greater than the rate of return of wage labourers.

As Jeremy Rifkin pointed out, the concentration of ownership of means of production by the capitalists and the subjugation of labour to capital was what defined the class struggle of the 18th century (Rifkin 2015). During which, the transformation of land from commons to real estate also lead to enclosures of resources that are driven by self-interests. In present times, these enclosures

become private investments for speculation controlled in the hands of the rich and with little access from the other layers of society.

Within this discussion of ownership, access and enclosures, how does Architecture fit into the picture?

History of Retail Form

Evolution of the Marketplace

Architecture cannot solve inequality. But, it is important to recognize architecture as a crucial jig in the whole picture. It is the crystallization of the outcome of the economic, political, and social of inequality. It is the environmental manifestation of inequality.

What it can do is to provide and improve access into these enclosures. This book seeks to divulge the urban marketplace, namely the shopping malls of Orchard Road, as a common, shared space for the exchange of goods, services, information and culture. It is about

diversifying enclosures for different communities to exist together on the ground plane. By doing so, we seek to dissect the exclusive and inclusive nature of certain enclosures. These terms of ‘exclusivity’ and ‘inclusivity’ are used as neutral terms, denoting the

private and public nature of the enclosures which could be for any heterogeneous communities in a space, going beyond the stratifications of the rich and poor.

The essays in the book are written to be read individually, but have been arranged to be read as a totality and in sequence. It is segmented into 3 main sections to understand the relationship between inequality and the ground.

Firstly, the first part (including this essay) attempts to position and situate the discussion of inequality in

architecture, transposing the issues of ownership, access, enclosures and exclusions/inclusions on Orchard Road for a better understanding of these issues in relation to the architectural space of the marketplace as a social space.

Secondly, the Where’s the ground section investigates the relationship between enclosure of space due to negotiation of the ground plane and the inequality of accessibility. Specifically, it studies the circulation, typology and the microtopography of the ground plane.

Thirdly, the final section summarizes the understanding of exclusive and inclusive enclosures and their relationship with the ground and the different communities. It also concludes with a set of operations for negotiations with the ground plane in order to create better enclosures for people.

Situating Inequality

OWNERSHIP IN ORCHARD

Spectacle of Retail

Platform of needs and wants

Multi-faceted Ownership

.jpg)

.jpg)

Orchard Ownership

Various Ownership models

Orchard Road is more than just a retail street for tourists.

It is a strip of nuanced identities and ownership. Behind that Singapore Tourism Board-curated world-class image, it is home for the rich and famous. Yet, it is also a spot for youths to hangout in. On one end of the highly curated streetscape, there are international fashion brands fronting duplexes or even a Southeast Asian first Cartier triplex. Yet, across the street, you also have dingy fast fashion incubators embedded inside strata-titled malls. At night, it is a watering hole for expatriates, the rising middle class and white-collar workers seeking for happy hour. Yet, happy hour also has other connotations in different stretches of Orchard Road where you have nightclubs, KTVs and social escort or prostitutes for men seeking fun. Its tree-lined streetscape is not only a tourist trap but a trapping of different communities desired and undesired, co-existing together on a single plane: the ground.

Its multifarious nature is perhaps due to the myriad of owners in Orchard. It is perhaps one of the most multilayered ownership models in Singapore. It is the birthplace of some of Singapore’s top real estate developers like Far East Organization who owns the largest collection of properties in Orchard, owning the firm the title of ‘King of Orchard’ (Far East Organization 2018). Other local developers include City Developments and Hotel Properties Limited. It is also a property stronghold for many foreign companies like Hongkong-based Wheelock Properties, Australian-based Lendlease and Malaysia-based Starhill REITS (Whang 2015). Even the King of Brunei owned a slice of Orchard Road together with the Thai Embassy a few blocks away. Other than these heavyweights, there are also

ownership models for the middle-class in the form of strata-titled malls and Real Estate Investments Trusts (REITS) like Fraser Property, SPH REITS and OUE REITS (Whang 2015). As such, such ownership models also give an opportunity for small to medium-sized investors to own a slice of Orchard Road.

Having said that, however, due to the diverse owners profile cramped into a prime 2.2 kilometres strip, it is also a battleground of ever-increasing rents, profits and footfalls.

History of Orchard Road

Palimpest of Time

Historical Development of Orchard Road

This diversity of ownership did not just happen overnight but built on layers over the course of 200 years.

1800s: Hillside Plantations

In the 1800s, Orchard Road was an unnamed road running across the valley with acres and acres of plantations, namely gambier and nutmeg. The nutmeg plantations were largely owned by the British, prominently William Cuppage, William Scotts, etc (National Heritage Board 2018). When the plantations were destroyed by beetle infestations, many of the land were subdivided into smaller pieces and sold to wealthy Asian families and banks who built bungalows for their high-ranking staff to stay (Tan 2018). Gradually, at the Tanglin-end of Orchard Road, a cluster of bungalows were formed, creating a residential community.

Early 1900s: 1st Suburbs Town Centre

By the 1900s, Orchard Road became one of the first suburban Town Centre of Singapore. Orchard Road was the primary connection for the residential

community at Tanglin to enter the city (Tan 2018). It gradually became an important gateway to the business and commerce area near the Singapore River. With the growing residential population, the road started to sprout rows of shophouses selling daily commodities, car showrooms displaying the latest cars from brands like Audi and Cycle & Carriage (National Heritage Board 2018). It was the third place in which people stop by to get their sundries after work and before getting home. Hence, with little surprise, Singapore’s first supermarket, the Cold Storage was founded here which in turn morphed into Centrepoint we know today (Tan 2018).

1960s to 1990s: Singapore’s Retail Hub

By the mid-1900s, Orchard Road became the place to go to get the latest fashion, trendy gadgets and a place to see and be seen. C K Tangs opened one of the earliest departmental store. The Shaw brothers introduced cinemas to Orchard road (National Heritage Board 2018). Far East Group brought Singapore’s Orchard Road to the world map with the opening of the world’s first multi-storey, fully air-conditioned shopping centre, Lucky Plaza

(Far East Organization 2018). It was also the birthplace of the first Macdonald in Singapore, giving rise to a generation of youth that frequently hangout in the vicinity (National Heritage Board 2018). It was an inclusive public space for all to exchange goods and services.

Present Day: International Fashion Street

By the mid-2000s, as the city embarked on a policy of decentralization, masterplanned in 1991, Orchard Road’s role as the prime retail hub for Singaporeans also started to decline (Ng 2015). Regional centres were established out of the city in Tampines, Jurong and Woodlands, bringing the convenience of shopping to the doorsteps of the population. Coupled by competition from e-commerce, Orchard Road continuously seek to rebrand itself: a world-class international fashion street. Yet, the outcome of the image is a homogenous streetscape that seemingly caters to the likes of the tourists while having little tolerance for different sub-cultures, communities or even locals that in the past frequent the area.

Competitive Nature: Survival of the Fittest

Competitive Nature

Measure of intensity of refurbishments

Due to the diverse portfolio of owners, Orchard Road had become a battlefield of property ownerships,

jostling to attract the highest footfalls of visitors. This is illustrated in the diagram above that tracks the past decade of building refurbishment in Orchard Road, amounting to a total cost of approximately $982 million. This is probably catalyzed by new retail entries to the strip, namely Ion Orchard at Orchard MRT Station, Somerset 313 and Orchard Central at Somerset MRT Station in 2009 (Ng 2015). After which, the strip saw several number of properties in the vicinity of these new entries undergoing refurbishment like the Shaw House, Mandarin Gallery which added retail shops to its otherwise hotel block. These building refurbishments are retrofitting

projects which increase the gross floor area (GFA) of the building by the additions of new wings, levels and/or increased shop frontages (Ng 2015).

None of the projects are demolition projects. Hence, in order to compete with one another, the owners have to constantly upgrade their properties and not completely demolish as it would increase the cost significantly (Ng 2015).

Building refurbishments are a common way to increase GFA (Ng 2015). It is one of the methods REITS and single owners used to increase their distributions and profits. With increased GFA, the owners would have additional net lettable area to increase the pool of tenants while refreshing the mix and image of the mall. This in turn allows them to increase their rental

income by also increasing the price of rents. Ultimately, it is about increasing the profits and dividends of their properties. In order to increase GFA, the owners can deploy several methods: to leverage, to backfill and to decant.

To leverage

Property owners commonly utilize state incentives to increase GFA. Several incentive include outdoor

refreshments area scheme, art incentive, covered walkway and community uses incentive to squeeze additional floor area for increased rents. For example, building within 400 metres of an MRT station within the city centre can reduce up to 20% of their carpark lots and transforming the floor area for commercial use.

To backfill

Another loophole often exploited by developers is to backfill soil into basement areas of low-yield spaces like excess carpark lots and back-of-house service areas (Ng 2015). In doing so, the GFA can be transferred for other higher-yield purposes like retail.

To decant

Similar to backfill, low-yield spaces in a tower block can have their floor slabs gutted out in order to transfer the GFA for more productive uses (Maybank Kim Eng 2018). For instance, office spaces fetches lower rental income than high-end fashion retail spaces. Hence, to increase the yield of rental from fashion retail spaces, several floors of offices can be decanted for more GFA in the retail segment.

Methods to grow distributions

Leverage, Backfill, Decant

The resultant of these actions are 2-folds.

Firstly, it is about constantly increasing rents. As rental space increases, the price of products would inevitably be increased, leading to rising cost of living. Secondly, it completely disregard the architectural tectonics and experience of spaces. In all, it created a vicious cycle of continuous addition and removal of spaces which is profit-driven and community-depriving.

Therefore, in Orchard Road, with its wide range of owners, there are many self-interests at stake with different priorities. This resulted in different decisions made by owners in building different forms of enclosures. Some solely favour exclusivity for the privileged while others aim to include. The different exclusivity and inclusivity of the enclosures in turn attract and deter different communities to take roots or expelled. This leads to faceted situations like derelict buildings due to strata-titled ownership, underprivileged service staff, undesirable maids and prostitute co-existing and slowly encroached by the private enclosures of hotels, high-end residences and exclusive clubs. Consequently, this creates multiple identities hidden underneath the heavily promoted tourist-driven imagery of Orchard Road.

Where's the Ground?

A STUDY OF CIRCULATION AND TYPOLOGY

Retail Form

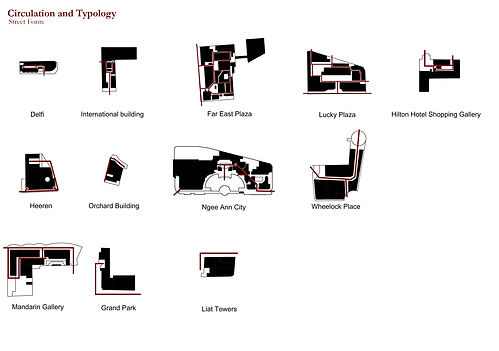

STREET FORM, ATRIA FORM, HYBRID FORM

Circulation and Typology

The street is the urban glue of communities (Jacobs 1992).

A study of 25 malls of Orchard Road was conducted to understand the relationship of the pathway and the consumption space. The pathway refers to the horizontal surface people traverse on, regardless indoor or outdoor. This is analysed in relation with the consumption space adjacent to the pathway, be it retail units, social spaces, outdoor public spaces. This set of study help to elucidate the accessibility of a particular space to users, shedding light on the elements of forming exclusion through circulation and typology.

The malls of Orchard Road can be summarized in 3 typologies: Street Form, Atria Form and Hybrid Form. Each of these forms have different psychological effects on the users in the particular space, causing people to either treat the space as a destination

(welcome them inside) or a travel (walk past). From a retail point of view, thereafter, different brand levels of goods and services are then programmed according to the space. Alternatively, the different width of the pathways may also be used as public spaces for sitting, gathering or solitude.

Street Form

Circulation and Typology

Street Form

The most common typology is the Street Form. The street-form typology offers a prescriptive route to curate one’s experience in that particular space. The pathways can range between 1.5m to 4m. They can be found largely on the ground plane and also basement levels of the malls, having a ceiling height of 3m to 4.5m. With such dimensions, they created a scale in which that is directional, meaning the space becomes a traverse space. It is usually a corridor, boulevard for people to walk through, rather than stopping.

In addition, with such a scale, it also frame views through faceted façades and elements that mark the start and end of the pathway, creating a series of forced views that may entice people into the adjacent spaces. With such narrow width, it also brings people closer visually and physically to the adjacent spaces, thus having a view into the displays of the retail units, drawing people in. Thus, this form has high degree of control on the sightlines and the circulatory path of people. At times, particularly in the basements of Ion, Wisma Atria and Ngee Ann City, people are also observed to have a faster walking speed as they are directed to their destinations. Hence, it is also observed that such pathways are usually found in areas for mid-range to low-end goods but not exclusive to this range of brands. In all, the street-form typology recreates a controlled version of the vibrant outdoor streetscapes indoor.

Atria Form

Circulation and Typology

Atria Form

The atria form offers an exploratory circulation that circumvents around the atria space of the mall. The pathways are not so clearly defined horizontally as its edge is blurred by the atria, ranging from 3m to 9m wide. The pathways usually are found at the periphery of the atria or a few atrium and have higher ceiling heights than the street-form typology. The shape of the atria would determine the direction of pathway. A square atria will have more rectilinear pathways compared to a circular atria. With such dimensions, the pathways formed a looped discovery that keeps people continuously traversing on the path.

With its 3 to 4 storeys high volume, it tend to bring people’s sightlines upwards in awe and to locate and be excited by the different floors of happenings. Such pathways can be found in atria-form malls like Ion Orchard which caters to mid-end to high-end customers. Such typology have relative control over the choice of paths of people, rather it subconsciously trap people in a loop within the building.

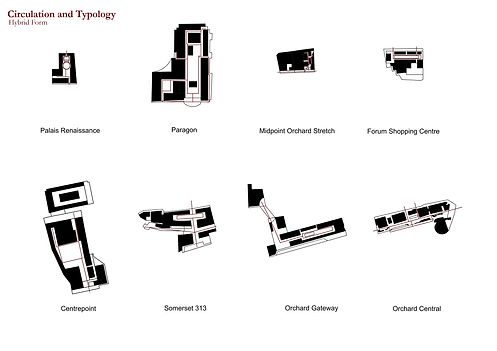

Hybrid Form

Circulation and Typology

Hybrid Form

The Hybrid form is a combination of both street-form and atria-form. This occurs when the atria size is small (not more than 10m) and/or the pathways are wide (2.5m to 4.5m) and thus, forming eaves of the floors below. Due to the hybridization, the pathways are semi-directional, yet also promote free circulation. The experience of such space is akin to a stroll in a park.

Such form can be found in specialty-centric malls like Palais Renaissance, Forum Shopping Mall. Due to its hybridization, the form offers a series of compression and release of large and small spaces for directionality and also respite.

Sight and Signage

View points

Sights and Signages

These typological forms also have effects on a user’s perception of the space. The outcome of these forms affects the sightlines of the user as he circulate in the space and in turn how he behave within it. The perception of space contributes to the psychological understanding of the scale, giving a sense of intimacy of the space. Hence, the perception and psychological understanding relates the user to the extent of inclusivity of the space.

There are several ways to accentuate sightlines by creating certain viewpoints. Views of the shopfronts can be directed by angled window displays that capture the users’ attention, thereby attracting them to the shop. In addition, certain facades of the shop can be faceted to increase the cone of the sightlines of the user. At certain points of the circulation, certain façade can be curved, multi-faceted to emphasize on the importance of the space and may even create a sense of arrival to the space.

This is more evident in a street form typology. By doing so, it curates the experience of the users while traverse the different circulations created by the typological forms. Sightlines value add to the experience of circulation.

While the street form may induce more horizontal sightlines, an atria form tend to lead one’s sightline up vertically. The atria form tend to draw one’s viewpoint upwards, revealing certain elements like the signages of the brand names, circulation points and etc. The atria fulfills its role of being a space in which users can familiarize themselves with its circulation. This understanding improves one’s understanding of the various spaces in the building, giving a sense of direction in an otherwise free-form space. That sense of understanding of the space contributes to what the user perceive as inclusivity. Therefore, it improves the imagery of accessibility in space.

Street as Public Space

Kits of Parts

Kits of Parts

In the study of circulation and typology, accessibility of space through circulation is largely due to the typology of the malls analyzed. In order to understand the relationships within these circulatory spaces, they can be further dissected into separate elements namely: Pathways, Spatial Elements and the Form of Atria.

Pathways

The dimensions of the pathways analyzed ranged from 1.5 metres to 20 metres. These pathways can be found within the building or in the exterior of the building. The different dimensions are observed to serve different purposes of the building. For instance, in a space that is meant to be directional, a 1.5 to 2.5 metres width corridor is used to induce circulation while in a high-end mall like Ion Orchard, a 4.5 metres circulatory path will be used instead, together with higher ceiling heights. In doing so, a grander retail experience is created. When the pathways get to a dimension of 7m to 20m (commonly outdoors), the circulatory street can become a public space that is no longer directional but a destination.

Spatial Elements

Architectural elements like walls, doors, columns, railings can further add on to the experience of the pathways. The materiality of the elements can change people’s perception of the scale of space, for instance, making them feel more spacious in a space with glass frontages and glass railings. Other elements include steps, niches and landscaping. These elements can also be temporal, flexible fixtures like pots of plants, advertisement boards, etc.

Form of Atria

The geometry of the atrium spaces can also contribute to the experience of the pathway. A square, circular or rectangular atrium with varying dimensions can affect the scale of the pathways adjacent to the atrium. For instance, a square atrium will result in more rectilinear pathways while a circular atrium can provide a relatively free circulation that traps the user in a loop (Paknejad 2017).

Assemblage

The compilation of the separate elements of pathways, spatial elements and form of atria then create a sense of direction or destination within the typological forms which in turn determines the inclusivity of the space and its surroundings. For instance, in the directional model, despite having glass frontages, a narrow 2.5 metre wide corridor with a 15 metre circular atrium space would deter users from entering the shops. This is evident in the basements of Wheelock Place. Instead, due to the narrow dimensions and lower ceiling heights, it becomes a directional space that induce people to circumvent the space to approach upwards or downwards the atrium.

In another example, an 8 metre pathway can be separated into 2 pathways by having temporary spatial elements like potted plants placed in the middle. This can be illustrated in Paragon Shopping Centre. By doing so, the mall has created a dual-directional pathway for users circulating the space in opposite directions. In addition, it brings the users closer to the shop frontages, giving them a clearer and more enticing view of the displays.

In addition, the recent addition of Apple store at Knightsbridge, Grand Park Hotel also introduces an outdoor public space to the streets of Orchard Road. With its overhanging glass roof and high glass frontages, it helped to interface with the 7m widelandscaped pedestrian street at its front. 6 to 8 trees were planted with the provision of a pair of benches. In doing so, the store has create a destination public space in the otherwise directional streetscape. Simultaneously, such an assemblage invites the people into the Apple Store, making the interior shop as an extension of the exterior public space.

Exerting Exclusivity

Exerting Exclusivity

Strategies and methods

The assemblage of these elements also can exert exclusivity over one’s approach to the space. An entrance with elements that increases threshold may deter certain groups of people from entering, navigating or even locating the space. This can be summarized in the following 5 strategies.

1. Contradictive Archetype

The building form and/or spatial typology creates a visual mask that covers the intended use.

2. Stealth Mode

Invisible / Visible barriers that deter people fromentering a space that is hidden from view.

3. Labyrinth of Obstacles

The sequence of circulation is convoluted with obstacles that make the space seem accessible.

4. Mental Dead Ends

Certain elements may attract the sight of people and cause certain sightlines to be blocked.

5. Jittery Thresholds

Certain entrances are designed to create a sense of privacy that psychologically hinder entry. Through these strategies, the class divide between the different communities are constantly negotiated.

Nolli Map

Nolli Form

Community and Congregation

Through the study of the circulation and typology, we could start to stich the various typological forms into a Nolli map. A ‘Nolli Map’ of Orchard Road reveals and clarifies what is public and what is private but here, it also informs how accessible a space is. Highlighted in black are the obstacles that further accentuate enclosure of the void in white. Other than understanding its circulation, large void areas start to suggest public spaces and gathering spots for different communities in Orchard Road. The Nolli Map not only reveals the accessibility of these spaces but also how the elements shaped those enclosures.

However, it is also important to note that the ground plane of Orchard Road is not flat.

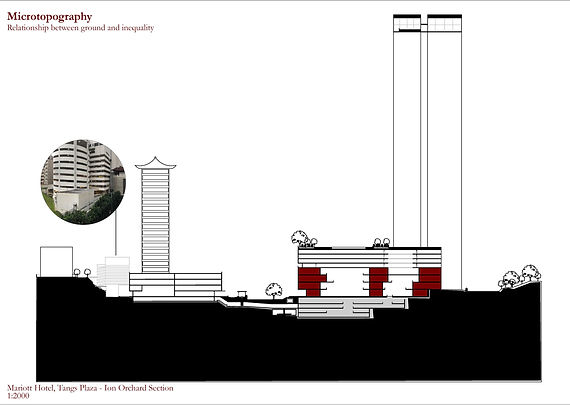

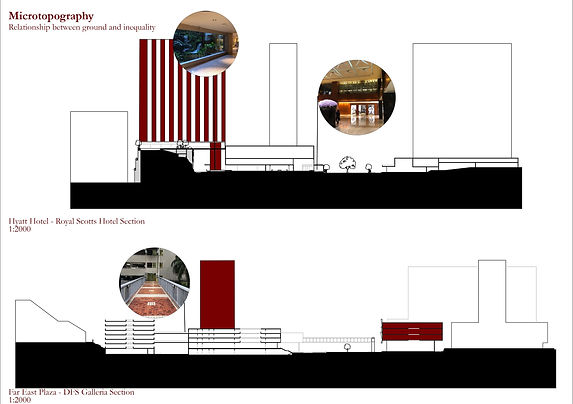

An inquiry into Microtopography

Orchard Road is situated in a valley of hills.

It is at a confluence of Claymore hill, Cairnhill, Emerald Hill and Mount Elizabeth. A stream, renamed as the Stamford Canal in the early 1900s, runs in between the undulating terrain. As such, the ground of Orchard Road is not flat as perceived from the streetscape of Orchard Road. Instead, hidden behind the 2.2 kilometres of malls, there are 6 to 18 metres elevation of the ground plane. As a result, the strip of buildings are sitting on uneven ground.

An investigation was conducted to understand the relationship between the microtopography and enclosures in Orchard road. Microtopography refers to the small changes in terrain ranging from 1 metres above the ground plane to 18 metres. Due to the differential changes in the ground plane, the buildings are studied to understand how they negotiate with the terrain. Consequently, due to how the buildings sit on the terrain, certain enclosures are planned or unintentionally manifested. These enclosures refers to spaces that are formed due to the decision made by the owners in relation to the negotiation of the terrain. These spaces can display a sense of exclusive or inclusive depending on the programme and the people occupying the space. A series of sectional cuts are utilized to understand this relationship between the ground and the enclosures.

Microtopography Section

Reaction to the Elevations

Concorde Hotel and Mall – Stamford Canal Section

This sectional end of Orchard is largely flat. The building digs down by 1.5 to 2 metres, creating a 2 storeys retail podium that is semi-sunken into the ground. Consequently, a new artificial ground plane is created as the hotel portion is lifted and sits on top of the podium block. In doing so, it helps to separate the hotel guests from the shoppers, giving a sense of privacy for the hotel guests above. At the same time, the base of the hotel tower helps to give the sunken retail podium some form of enclosure for the shoppers, creating a 4 metres wide sunken pathway as a more private circulation that is connected to the bustling main streetscape of Orchard road.

On the other end of the building, a 10 metre raised plinth, flanked by other buildings, becomes a courtyard space of the area in which service staff of the hotel use as a spot for smoke breaks. In addition, a semi- sheltered hawker centre adjacent to the courtyard space serves as a lunch spot by day for the service staff in the vicinity and a eating spot for tourists by night. In this way, the building’s negotiation of terrain by sinking its retail podium 1.5 metres into the ground, created different zones of enclosures for different groups of people in the day and night.

Centrepoint – Orchard Central / Orchard Gateway Section

In this sectional cut, the buildings start to dig down the ground to create 2 to 3 levels of underground basement while connecting 3 differently owned malls together with an underpass that cuts through the boulevard at grade level. This underground connection is programmed with food and beverage functions, providing users a plethora of dining choices as they traverse through the space to get to Somerset MRT station. Centrepoint (owned by Fraser Property REITS) has recently revamped its section into a 3 storeys sunken atrium space for better visual and physical connection to the underground food hall. In doing so, it also promotes higher footfall into its mall.

This section also compares the 2nd most horizontal shopping mall (Centrepoint on the left) on the Orchard strip with the 2 most vertical shopping malls (Orchard Central and Orchard Gateway on the right). In a vertical form, the retail space cannot be layered linearly similar to the horizontal form. Instead, the enclosures of space are organized by voids. In the case of Orchard central, different voids are designed in different levels of its vertical form with the void on the ground plane due to the need to negotiate with Stamford Canal running below it (DP Architects 2012). Through these voids, different zones of retail can be programmed. For instance, it has a gym in the upper levels, dining area in another section of the upper levels, a separate zone for beauty and salons and etc, creating exclusive spaces for different target groups of shoppers.

Microtopography Section

Reaction to the Elevations

Robinsons The Heeren – Scape Section

In this section, the buildings start to negotiate with the slight elevations of the ground plane. The buildings are built on the foots of Cairnhill with a topographical change of 1.5 to 2.5 metres. Due to this difference in height, Robinsons The Heeren has a ramped pathway leading to the office block behind and also a connection to the office block on level two but leveling on the ground level when it approaches the office block. This way, it separates the office block from its retail podium by having both blocks sitting on different elevated ground, creating separate enclosures for office staff and retailers.

On the other end, the youth-populated Scape created a gentle ramp that draws people into the mall at the second level. Flanked on both sides of the ramp, slight depressions were made to create small sunken plazas for the F&B kiosks. Thus, as it negotiate with the terrain, small-scaled, intimate spaces are created under the lush greenery, giving a sense of privacy for a more inclusive enclosure.

Microtopography Section

Reaction to the Elevations

Tangs Plaza – Ion Orchard Section

The terrain shows a larger degree of undulation due to the hill behind Tangs Plaza and the hill in which Ion Orchard is built on. In the case of Tangs Plaza, the building chose to disregard the terrain by flattening certain portions of the terrain while building its carparks ramp at the back of the building to level with the terrain behind. Ion Orchard, on the other hand, was designed to utilize the terrain. The building concealed the terrain within its building. By doing so, at the front of the building, it is raised several steps above ground while having a gentle ramp to a drop-off behind. The raised steps become a space in which visitors would sit on, making it a public plaza. The drop-off behind leads visitors into the mall at the second level. In doing so, the circulation of shoppers are in a loop as they traverse around the atria form typology of Ion Orchard.

Microtopography Section

Reaction to the Elevations

Hyatt – Royal Scotts Section

In negotiating the terrain, Hyatt Hotel took a different approach in comparison to Tangs Plaza. Hyatt Hotel has 2 separate wings of hotel rooms that are connected by a bridge. The bridge is an architectural element that reconcile with the terrain by jutting it out from the hotel wing built on the hill that is 12 metres higher then the Orchard road ground plane. This way, it respect the terrain with minimal alteration to the landscape. In addition, the carpark below the bridge is slightly ramped, following the contours of the topography. Due to such intervention, a waterfall feature had been added at the higher plane of hotel wing, flowing water down to the hotel wing at the ground level of Orchard Road, creating an environment of respite for the hotel guests. This adds onto the luxurious ambience of the high-end hotelier brand.

Palais Renaissance – Hilton and Four Seasons Hotel Section

Similar to Hyatt Hotel, Hilton and Four Seasons hotels sit on a terrain that range from 1m to 12m. Four Seasons Hotel is built on higher ground behind Hilton Hotel. To provide a convenient access to Orchard Road, the owner connected both properties, giving Four Seasons a direct access to the bustling streetscape of Orchard road.

However, this access mitigated by the bridge connecting the two properties also create an exclusive enclosure that conceal a high-end retailer owned by the wife of the property. Therefore, although the building is built as a hotel typology, a large proportion of Hilton’s podium block and the bridge hides away a series of high-end brands like Issey Miyake and Comme des Garcons. In addition, a series of thresholds are created for a visitor to access Four Seasons Hotel. Firstly, the visitors need to be aware of the existence of such a connection and to be able to navigate the labyrinth of circulatory paths in order to arrive at the Four Seasons hotel wing. Thus, it created a highly exclusive zone catered almost solely to the hotel guests.

.jpg)

Negotiating Topography

Form and Split-level Typology

Lucky Plaza

In the case of Lucky Plaza, the building had to negotiate with the raised 4.5 to 6 metres terrain. In order to do so, the building created a service road leading to the car park while providing a bridge to connect to a separate entrance for its residential block on the retail podium. This not only adds privacy but also security for the residents. In addition, the building is built in alignment with an elevation of the ground by 1.5 metres. As such, the other end of the building is slightly higher than the aligned end. This 1.5 to 2.5 metres difference in gap created an opportunity for direct split access to the basement and the first level of the retail podium. This in turn helps to increase the traffic footfall into multiple levels of the mall.

Public Form

Plaza and elevation

Microtopography Operations

Augmenting Form

Negotiating the ground

Through the understanding of the relationship of microtopography and ground, we can establish 4 operations in augmenting the ground to create enclosures of exclusivity/inclusivity: 1) to undulate 2) to conceal 3) to create 4) to retain.

To Undulate

It is to dig and raise the ground through a series of depressions and elevations to creating pockets of public spaces. This can be done on flat surfaces or up to 1.5metres of undulations. These pockets of spaces are commonly used as outdoor café spaces, pop-up stores or alfresco dining.

To Conceal

A change in level in the terrain can be hidden within a block, giving an impression of being a single level while having connections at 2 levels or more. This is common for negotiating a terrain at 4.5 to 6 metres, allowing for a mezzanine or split level to be built. Architectural spaces like split level access are an outcome of such strategy.

To Create

It is to create a new artificial ground plane that separates from the true ground. This can be done on flat surfaces or on a terrain. In doing so, the uplifted artificial ground plane becomes a more exclusive space for people. This is usually seen in hotels which require the exclusivity for privacy and security of its guests.

To Retain

In respecting the terrain, the building is built on slits, therefore, touching the ground lightly. This is usually done in terrain with huge changes in the elevation of the ground. A plane jutting out of the terrain can connect with other buildings, forming a bridge for increased accessibility. In this way, it provide access in an otherwise highly exclusive, separated space.

How to Ground?

GROUNDING INEQUALITY AND CO-EXISTENCE

Fragmented Islands

Community and Formation

Grounding Inequality

Therefore, from the study of circulation, typology and microtopography, we can now understand how the different ownership models in Orchard Road drive different individual agendas and interests, thus negotiating with the ground plane differently. As a result, it created fragmented, siloed islands of communities that are confined within exclusive and inclusive enclosures. For better or for worse, these enclosures are either planned or unintended, it gave rise to a multiple of nuanced identities in an otherwise banal tourist street.

Orchard Road is not as flat as we think it is.

Strategic Section

Negotiating Microtopography

Co-existence

Urban Form of Retail

Pratunam Market

Putting forth a potential for co-existence, a study on Bangkok’s Pratunam Market shows the tolerance of different stakeholders living, doing business and exchanging in a single flat plane. Through different kits of parts, vendors are able to co-exist within the fabric of the urban block and its surrounding large scale retail developments. Thorough spatial elements of the shop dimensions, roofscape and streetscapes, Pratunam Market has established a model of

co-existence for small business to thrive in a shopping district typified with rows and rows of shopping malls and shopping centre. In fact, they co-exist in a symbiotic ecosystem in which the Pratunam Market functions as a fashion wholesale centre for the malls, facilitated by tuk-tuks as logistics transporters and food peddlers as the mobile canteen of the market.

Hence, the formation of inclusive and exclusive enclosures is crucial to the expansion of such communities. Be it rich or poor, some form of exclusive enclosures can allow communities to take roots and thrive. At the same time, inclusive enclosures can facilitate the confluence of different communities to come together and share ideas, culture and resources. The study of the circulation, exerting exclusivity and strategies in augmenting the ground becomes useful tools in the formation of such enclosures. In addition, they can be used to suit different intents and interests, applied to different situations, for a myriad group of people and catalyzing different activities through the course of time.

.

Community Building

Kits of Parts

So, enclosures are not bad.

Neither is it about the enclosure being exclusive nor inclusive. Instead, to provide access and even out

inequality, it is about the interlinkages and interrelationships of the enclosures.

The co-existence of exclusive and inclusive enclosures is paramount to providing access to resources and space.

Therein, levelling the uneven grounds of inequality.

Making retailspace

Roofs and Alleyways

References

WHO I QUOTED

DP Architects. 2012. DP Architects on Orchard Road. Australia: The Images Publishing Group.

DPM Tharman Shanmugaratnam, ie. 2018. “The toilet attendant, the disinvited speaker and the moving escalator .” IPS Conference: Diversities, New and Old. Singapore: The Straits Times.

Far East Organization. 2018. Landmarks: 50 years of Real Estate Development. Singapore: Far East Organization.

Jacobs, Jane. 1992. The death and life of great American Cities. New York : Vintage.

Martin, Reinhold, ie. 2015. The Art of Inequality: Architecture, Housing and Real Estate (A Provisional Report). New York: The Temple Hoyne Buell Center for the Study of Architecture.

Maybank Kim Eng. 2018. Singapore Retail REITS: In need of retail therapy. Singapore : Maybank.

National Heritage Board. 2018. Orchard Heritage Trail: A Companion Guide. Singapore: National Heritage Board.

Ng, Josh. 2015. Building Refurbishment- How Commercial Building Owners Increase their Real Estate Value: Special Case Studies of Singapore Marina Bay Area and Orchard Road. Singapore: Partridge Publishing.

Ong, Ye Kung. 2018. “Working towards a more equal society.” The Straits Times. Singapore: The Straits Times, May 16.

Paknejad, Navid. 2017. “The phenomenology of shopping malls, a model for typology of shopping malls characteristic.” Researchgate.

Piketty, Thomas. 2017. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

2018 . Regardless of Class . Directed by Sharon Hun. Performed by Janil Puthucheary.

Rifkin, Jeremy. 2015. The Zero Marginal Cost Society. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Rousseau, The Discourse on Inequality. 2018. The Philosophy.com. Accessed November 9, 2018. https://www.the-philosophy.com/discourse-inequality-rousseau-summary.

Tan, Guan. 2018. “Orchard Road: How a Quiet, Hilly Valley became an Epicenter of Luxury Retail.” The New York Times Style Magazine. September 14.

Accessed September 29, 2018. https://www.tsingapore.com/article/orchard-road-how-quiet-hilly-valley-became-epicenter-luxury-retail.

Teo, You Yenn. 2018. This is what Inequality looks like. Singapore: Etho Books.

Whang, Rennie. 2015. Who owns Orchard Road? Singapore: The Straits Times.

Yahya, Yasmine. 2018 . “Singapore must ensure no one is left behind as the country progresses: PM.” The Straits Times. October 23. Accessed November 3, 2018. https://www.straitstimes.com/politics/spore-must-ensure-no-one-is-left-behind-as-country-progresses-pm.